FERTILE GROUNDS an interview with yussef agbo-ola

Yussef Agbo-Ola is not unlike the Shamans and Babalawos he so reveres. His works are conduits to the spiritual realm, oscillating between human and non-human life forms, in an attempt to restore balance between the two. He similarly acts as a middleman, working amidst and beyond the ecosystems of art and architecture. For Agbo-Ola, climate justice is less a hot topic and more of a life practice, owing to his Yoruba and Cherokee lineage that embeds these issues into the very fabric of his cultural inheritance.

Yussef and I catch up over Zoom. He is in his studio in London for a matter of days, before leaving to teach at Columbia Graduate School of Architecture. Agbo- Ola’s projects are abundant, yet his commitment to broadening the scope of ecological perception persists. In step with his two-fold practice, he was one of six artists commissioned for the British Pavilion exhibition at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennial. For this, he created Muluku: 6 Bone Temple, one in a series of four pavilion structures he conceives as architectural entities—live and inhabitable biospheres. In his prolific career thus far, he has designed art and architectural commissions for the Serpentine Gallery, Palais de Tokyo, ICA London, and the Van Abbemuseum, to name a few. In this conversation, Agbo-Ola discusses the value of entropy, decay, and impermanence, as well as the choice to cultivate environmentalism as the fertile ground for his design studio, Olaniyi Studio.

Oluwatobiloba Ajayi: You first studied anthropology, then art, before later arriving at architecture. What led you to these disciplines in the first place?

Yussef Agbo-Ola: I have always been inspired by culture, as I come from a multicultural heritage. My dad is Yoruba, and my mum is African American, but my great grandmother was Native American. I have a mixture of Cherokee Indian and Yoruba culture that has always been the foundation of my household.

So, I have always been interested in different belief systems, different epistemologies, and in the

different existential ways that people perceive the environment and the universe. That interest in culture really pushed me to study anthropology, and specifically, to the study of artefacts

that cultures create. That led me to then looking at the religious structures

that the artefacts would exist in. The architecture in which the sacred artefact rests is just as important as the artefact. Likewise, the program and the ritual that goes around the artefact is also just as important as the material makeup of

it. This interest in sacred artefacts and sacred architectural forms was the ideal life path for me as an artist and architect.

OA: You describe yourself as both an artist and an architect, and I was wondering how you feel about those labels. Your recent participation in

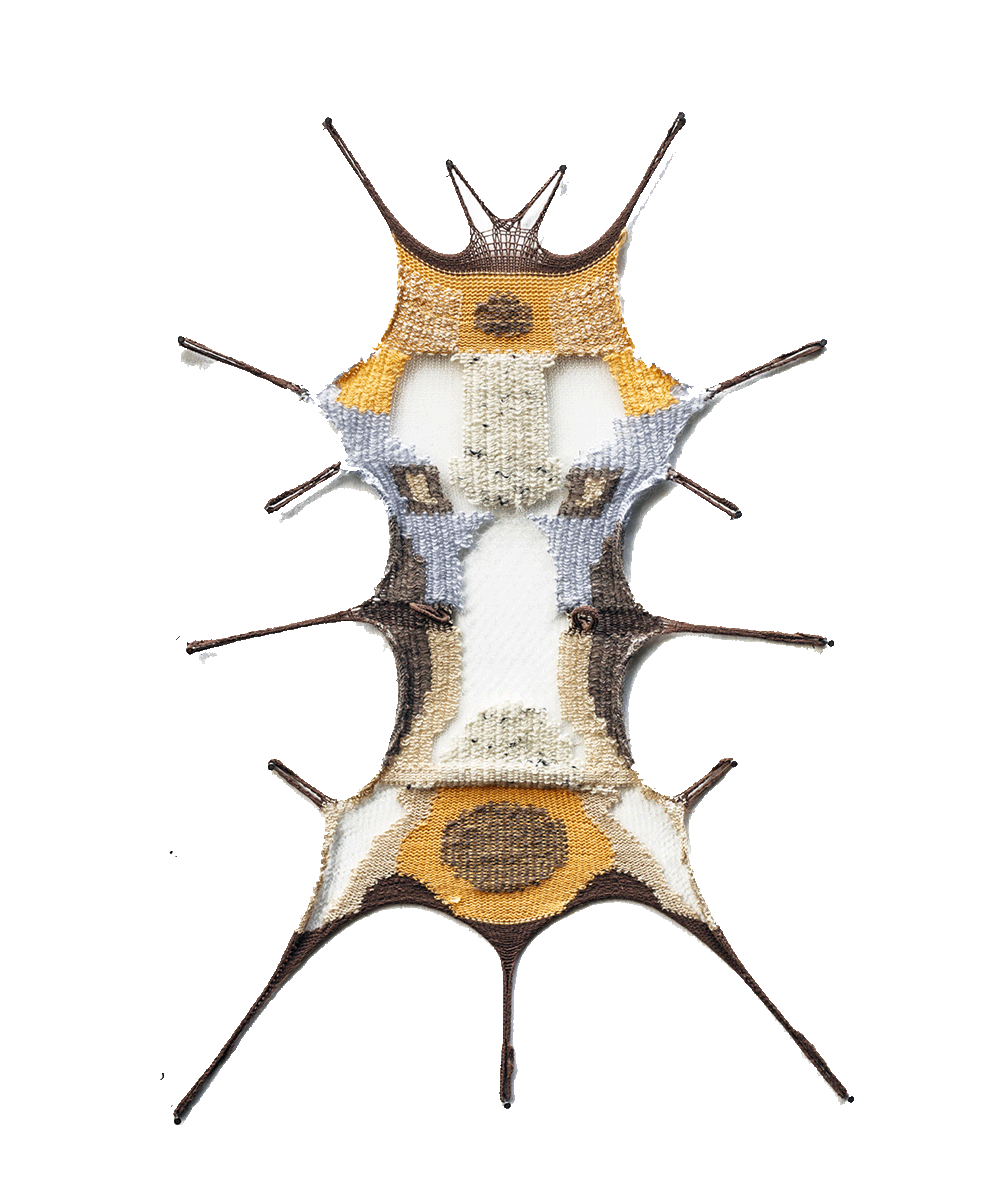

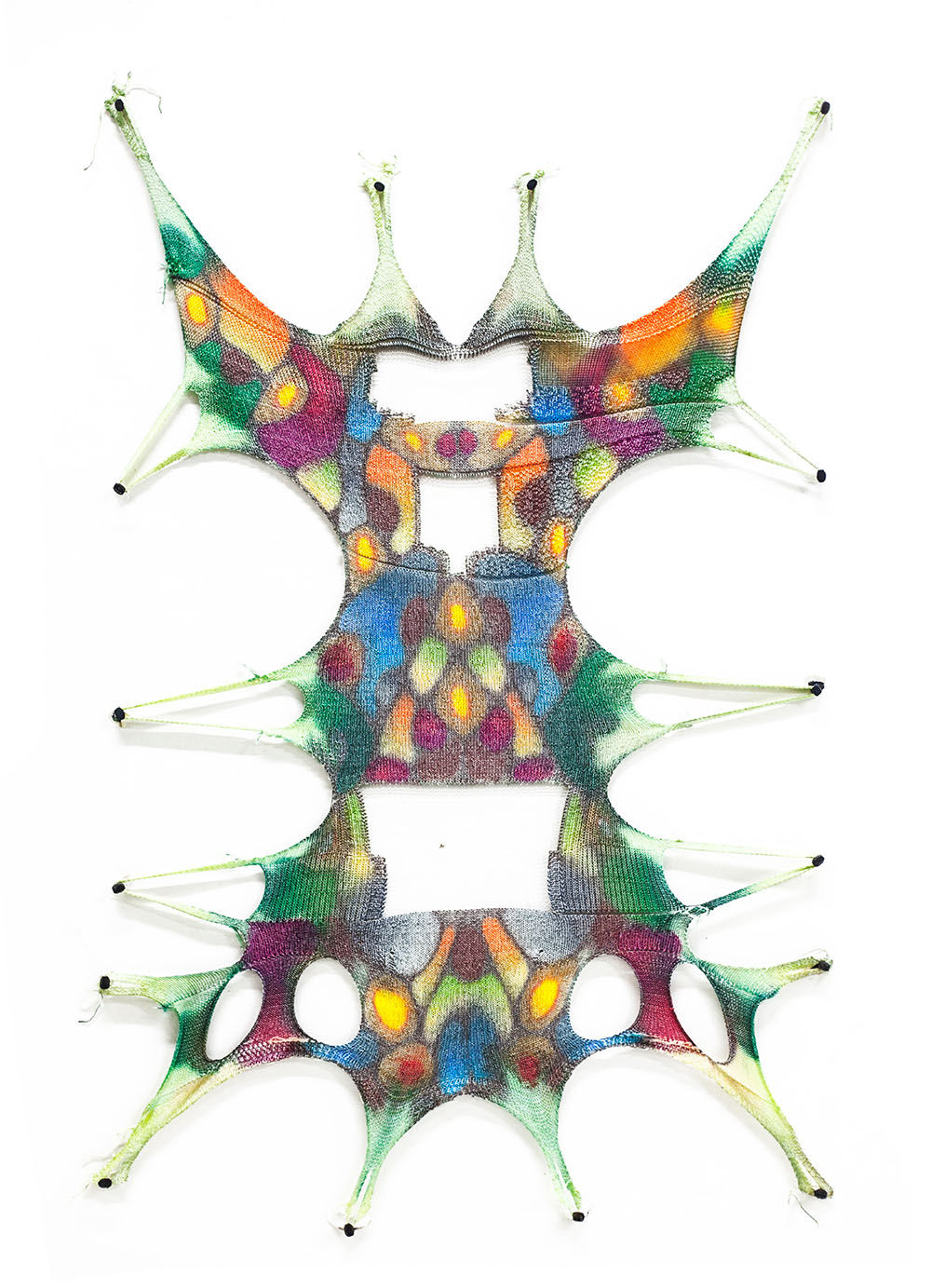

the Venice Architecture Biennial with your woven and stretched

‘Bone Temple,’ was a hybrid, multi-layered sculptural installation. How does your work challenge limiting definitions such as that of architecture?

YAO: It is a personal pursuit, honestly. I really battle with the idea of an architect and artist being separated, and it comes from my lineage into the field. When I look at tepees or different Native American structures, they are constructed

from fabric or animal skin, and you can say that is architecture. But then on

the animal skin you have all these motifs and paintings on the tepee that could be considered a traditional form of art making. I try not to divide the two labels. I don’t consider myself a traditional, solo thinking architect. I consider myself as a middleman between the two fields.

I think what really fascinates me between architecture and art is blending

the lines between scales. Scale is hugely essential to the practice of

Olaniyi Studio. In Muluku: 6 Bone Temple, I am working with

knitted yarn. One scale of the work is the human-scale, where you

can look through the temple and experience the different shadows. But if you look at the makeup

of the fabric, all those loops were inspired by the skin patterns at 50,000x what the eye can see. I am constantly looking at different organisms, endangered species, and looking at their skin patterns under the microscope, then mimicking the cellular patterns in the loop structure of the knitted sculpture. I try to take the micro realm and make it bigger, make it macro or architectural in scale. I appreciate both labels of artist and architect, but I know I work in between the two.

Architecture has more limitations than artworks. Architecture is a service-based profession—you have a client, and that client gives you some parameters and they say “Okay, create this!” I’m fighting against that notion. My work is service and functional based, but it is not necessarily client based. It is a living entity on its own, it is its own sacred object and has a presence beyond myself. The works are architectural in scale but artistic in its context and the way it exists and protrudes in the world.

OA: Could you talk a bit about your choice to prioritise environmentalism as a core concern of your practice?

YAO: Environmentalism is a super loaded word, crazy loaded. For me, it comes from a sacred understanding of devotion to the environment. I feel like the conversation around environmentalism has a lot to do with things that are external to us, but that is a Western religious notion, in the sense that we have domination over the environment. When I look at indigenous belief systems, they are more about reciprocity, exchange, and the constant feedback loop between us and the environment. There is no separate boundary between humans and nature. We are all intertwined in one complete system. It is a dynamic and adaptive process of observing and understanding your relationship to the environment, and it is a meditative practice.

Environmentalism doesn’t stop with the external environment. We have a mental ecology: the way we think, the way we perceive, what we take in. But I feel like the conversation around environmentalism is 90% external. It is about how we can generate energy, how we can control resources, how we can conserve different environmental systems, but a lot of times we don’t look at our own mental ecology. I believe that we can connect to our external environment the more that we connect to our internal environment.

‘‘THERE IS SO MUCH THAT WE ARE, AND THAT WE ARE A PART OF THAT WE CAN’T SEE. I HOPE TO EVOKE THIS REVERENCE FOR THINGS WE CAN’T SEE.’’

- Yussef Agbo-Ola

YAO: About entropy and change. Entropy is the rate of decay.

I spend about four and a half months every year in the Amazon, it is like my second home. When a tree falls in the forest, it becomes fertiliser for the soil, and opens up pockets of light. The light from the sun can then get to the opening in the soil, fertilise the new growth, trigger photosynthesis, and new trees can grow. There is this death of a huge tree, but through that death, the soil eats, and new plants can grow. That is super inspiring, so complex yet so simple at the same time. A constant exchange of metabolic energy on multiple scales: a multiplicity of energy exchange. It is a cosmos within a cosmos.

OA: The way you speak about exchange relates to how you talk about your own heritage, and how it helps you see the reciprocity between things. How has your heritage granted you a heightened awareness of the unseen?

YAO: I come from two cultures that believe in the unseen. I have just come from the Yemoja shrine in Ibadan. The Òrìṣà Yemoja, she is water, just water, just H2O. But there is an unseen spiritual energy that if you're Yoruba, or in the religion of Ifá, you believe you can access. It is an energy that you can absorb from the ocean, yet it is unseen. So yes, it is water, you can distil it into fresh water and drink it, which may be considered energy or life. But at the same time, you can

swim in the water and be completely engulfed by Yemoja which is also life-giving.

In Native American culture there is this idea of non-waste. Everything must be used. If you kill a deer to sustain the family, to eat, you become the deer through eating it. There is a chant you say because you recognise that the deer is part of a larger ecosystem, and you allow the deer to travel onto the next realm freely.

Even if you look at it from a scientific standpoint, no one physically with their eyes sees the process of photosynthesis. All we see is the tree growing, but we don’t see that energy exchange of the plants metabolising the sunlight. There is so much that we are, and that we are a part of that we can’t see. I hope to evoke this reverence for things we can’t see.

YAO: I have spent a lot of time with medicine men and women all around the world. Different shamans, Babalawos, and I think it is extremely inspiring the role these people play in understanding environmental epistemologies. They stay on the borderline between the seen and the unseen. A lot of the time, they are going to ancestors in the plants, rivers, or soils and communicating with them, then bringing that information back to the seen realm to either practice healing or share messages. The unseen is also about connecting with one’s ancestors. From my Cherokee and Yoruba heritage, it is about paying homage to your ancestors that you can’t see but you know are still there. There is the spiritual, the scientific, and the ancestral.

‘‘I’m trying to make my ancestors happy.’’

OA: PITU: Fertilization Temple (2023) Muluku: 6 Bone Temple (2023), Nono: Soil Temple (2022), and Ikum: Drying Temple (2022), are some of your structures that reference the textile and architectural traditions of your Yoruba and Cherokee lineage. These temples are sometimes paired with a soundscape, creating an immersive womb-

like enclave that forefronts the sanctity of the environment. Why are you drawn to the typology of the pavilion? How does it help communicate these ideas around spirituality, the reciprocity of life forms, and indigenous knowledge?

YAO: The tepee structure is big in Native American culture. Fabric use or skin use is big. Then the shrine in Yoruba culture is very important, it is a sacred space where these divine entities live and inhabit. I want to create sacred spaces that allow for reverence of entropy, decay, and change. The idea of the temple in some cultures is this monumental structure made of stone or brick that lasts forever—a reincarnation of the divine in a static architectural form. Yet the typology and material palette of my temples go directly against that. Instead of trying to concretise the divine in a static architectural form,

YAO: The final outlet for my temples is not the museum or the biennales, they are made to decay. They go back to the Amazon forest, and the cotton dye will change colour overtime. The plant climbers will take over the temple and different creatures will inhabit it. That is a mimicking of the entropy state of the divine. The temple takes on something that is more fragile and adaptive, to commemorate the beauty of uncertainty and the multiplicity of organisms. This idea of architectural death is extremely important to me. I am fighting against my own programming through architectural education of buildings meant to last for 50 years. What makes the temple sacred is the fact that it dies. Then it is reborn again with the help of environmental decay.

OA: This idea of ephemerality is present in some of your work, such as Plant Cellulose Skins + Aromatic Memory = Amazon Jungle, and Entropic Design “Kajola'' Footwear series.In the former, you attemptto capture smells, inherently ephemeral senses, in a sort of living archive. In the latter, you create shoes out of plant-based materials that will decay with use. Both projects are preoccupied with mutability: how to capture fleeting sensory experiences or how to introduce transience to a conventionally durable object. What draws you to these subversive design experiments?

YAO: These types of projects are the same push against the concrete. There is this idea of the art object being something that lasts forever, that it is an infinite untouchable object. There is value connected to the fact that it cannot be destroyed, it cannot change. So, I like the idea of the work subverting that, being something that is alive in a way. The object interacts with organisms, it can be eaten in a museum, or a gallery. I like this idea of uncertainty. I mean to go against the idea of permanence. The materiality of the work is not more important than the philosophy behind it.

‘‘If you can find out what that ‘why’ is, it will never fail you.’’

- Yussef Agbo-Ola

OA: You’ve done such a variety of projects, and you appear confident in your multi-faceted practice. What would be your advice for young creative practitioners who are struggling to balance all their interests, or are worried about how they all sit together?

YAO: Now is the most amazing time to do more than one thing. Join forces with people that share alike interests, collaborate with them, and start your own tribe. Be okay with experimentation and failure, find your own voice, then locate your ‘why.’ You have to find your own voice and hone in on what you want to say. For example, my ‘why’ is that I want people to connect to their environment. My path towards that is so many different things, but it is my ‘why’ that grounds me. If you can find out what that ‘why’ is, it will never fail you.

Credits

yussef agbo-ola & oluwatobiloba ajayi